Friday

22nd of November 1963: the day President John F Kennedy was shot

dead in Dallas Texas. The next morning, 5,000 miles away in the Welsh seaside

town of Aberystwyth, a seven year old boy and his younger brother, in matching

blue dressing gowns, got up early while their parents and baby sister slept on.

They listened to Tubby the Tuba on the large gramophone that filled the corner

of the dinning room. Then, sitting on the cold carpet, they turned their

attention to their Corgi and Matchbox cars, and pushed them along the fresh

snail trails that had appeared over night.

After

Danny Kay had finished telling the musical adventures of Tubby, the BBC Light

programme crackled out of the grey Roberts transistor radio. Like every other

Saturday, the boys listened to Uncle Mac’s Children’s Favourites. Squeezed

between the inevitable requests for Beatles, Gerry and the Pacemakers and Puff

the Magic Dragon, the news bulletin alerted the brothers to the death of John

Kennedy.

I

was that boy; I could not accept that Kennedy had died. My younger brother

asked who Kennedy was. I replied, all knowing and convinced that the President

of the United States could not be despatched, that it must be the President’s

brother. I knew that, although brothers were fair game, President Kennedy was

one of the good guys and was as indestructible as my black and white television

heroes, such as The Lone Ranger or Noggin the Nog.

Why

was the death of a president from a foreign country so important to a

seven-year-old boy in an era long before 24 hour news? In fact my brother and I

had not been exposed to much TV at all; we had only had a set for a few months,

to coincide with my father’s obsession to watch the cricket season of 1963 and his

long vacation from the University, where, as a violinist, he lectured in the

music department and led the string quartet. Then, just as the new autumn

schedule for kids started and TV began to look interesting, he had sent it back

to the hire shop and returned to his lecturing duties.

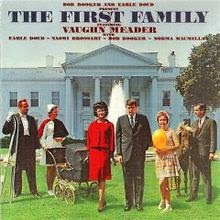

To

compensate for not having a telly, my father bought LPs of children’s stories

and songs for my brother and me and comedy for himself. One of his LPs was

called ‘The First Family’, and was a series of comedy sketches sending up

family life in the White House. My father played this over and over again,

until the story of Kennedy’s endless motorcade refusing to fill up at the gas

station because they didn’t issue green stamps had become as important to my

early cultural life as reading Dan Dare. After the shooting, the LP was hidden

away by my father, never to be played again.

Most

people in their late 50s and above can probably remember where they were when

they first heard about JFK’s untimely death. There are many websites devoted to

these memories, and it’s fascinating to see many of the contributors were young

children at the time of the assassination.

This

phenomenon is not limited to the death of one American President. My parent’s

generation knew where they were and what they were doing on the out break of the

second world war and since Kennedy, events such as the deaths of John Lennon,

Princess Diana and the first election victory for Tony Blair could also be said

to have left their mark on most people who were around at the time.

There

is something about traumatic events in childhood that stick in the mind. How

much of my recall of the Dallas shooting is genuine memory and how much is

guesswork is hard to analyse. Much of my story is pieced together from my

Saturday morning routines of the early sixties, I don’t know what I had for

breakfast that day or when I realized that it had been the President who had

died that day, and that his brother was to live on another few years before

suffering a similar fate.

Fifty

years on, my late father’s LPs lie in a dark cupboard, waiting for the time to

come when they are sorted out for distribution to the family or a trip to

Oxfam. Amongst them must be his copy of

“The First Family”, maybe enough time has passed to dust down the vinyl,

dig-out the old record player and give it its first play for 50 years.

1 comment:

A very perceptive description of the impact on a seven year old. I was just eighteen and in the kitchen early evening when I heard the news.

Would love to hear that LP.s

Post a Comment